A study published in the Annals of Emergency Medicine says 92% of the 48,835 clinically active emergency physicians in the United States practice in more urban areas, with just 8% practicing in rural communities.

Recent Posts

-

Trends in Emergency Healthcare: Go Locum, Go Rural

-

NP Scope of Practice vs. Independent Practice: What’s the Difference?

Discussions involving nurse practitioners (NPs) and their role in healthcare often include terms such as “scope of practice,” “independent practice,” and “prescriptive authority.” It’s clear these concepts encompass what an NP can and cannot do, but what’s the difference between each of them?

-

PA Licensure Compact Now Active in 7 States

Just this month, Virginia officially adopted the PA Licensure Compact, activating the agreement among seven states and decreasing the barriers PAs face when they travel and practice.

-

Report: Healthcare Facilities Across the U.S. Struggle to Fill PA Positions

Experienced and skilled physician assistants (PAs) are in demand across the country—and according to some PAs, healthcare facilities across the United States are struggling to keep up with hiring.

-

A Guide to Highest Paid Physician Assistant (PA) Specialties

Physician assistants (PAs) are an integral part of the healthcare system, providing many of the same services as physicians. With the flexibility to practice in any medical setting or specialty, physician assistants play a critical role in the delivery of high quality patient care. PA compensation varies depending on their specialization—read on to learn more about the top 10 highest paid PA specialties.

-

Checklist: What to Bring on Your First Locum Tenens Assignment

If you’re nervous about what lies ahead, don’t worry—that’s normal. We’re here to help you get your ducks in a row before you set off on your adventure.

-

Easiest States to Get a Physician Assistant (PA) License

There is one major obstacle that can hold a locum tenens provider back from working in new areas around the country: state licenses.

-

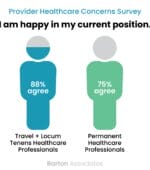

Survey Finds Travel Clinicians and Locum Tenens Providers are 17% Happier Than Permanent Peers

We recently surveyed our network of travel, locum tenens, and permanent physicians, nurse practitioners (NPs), physician assistants (PAs), dentists, registered nurses (RNs) and allied health professionals across a wide variety of specialties and found some interesting comparisons.

-

TSA Clothing Rules and Regulations: Locum Tenens Travel Tips

Locum tenens travel work can send you all across the country to interesting new places. This means you may find yourself on an airplane, which entails going to the airport, standing in an airport security line, and abiding by TSA clothing rules and regulations.

-

‘I Want to See a Doctor, Not a PA’: How to Talk to Patients Who Question Your Abilities

There are any number of reasons a patient may make the request to see a doctor instead of a PA, and it’s ultimately up to you to determine if you want to engage with the conversation further. Here are some of the strategies and talking points we’ve found to be effective.